Poker & Pop Culture: George Devol, the Ultimate Steamboat Sharp

We concluded last week with the thundering words of card sharp John Backus in Mark Twain's "The Professor's Yarn" echoing in our ears. "I'm a professional gambler" he loudly proclaimed after outcheating an opponent in a hand of poker aboard a 19th-century steamboat.

It's an emphatic line, suggesting not only that Backus believes himself worthy of the respect due to someone in his "profession," but also that being able to cheat successfully is in fact one of the requisite tricks of his trade. So, too, is the ability to defend oneself as Backus does by holding aloft his cocked revolver to accompany his words.

As we've already seen in our earlier survey of saloon poker, cheating was a constant in the 19th-century version of the game. The contemporaneous rise of steamboats and preponderance of poker and other gambling games aboard them even further established the "card sharp" as a highly recognizable character in American society, for better or worse.

If you think about it, if you were to cheat in a saloon poker game, your tenure there would likely only last as long as you were able to avoid being discovered. That would be the point at which the guns could well come out, and if you were lucky enough to make your exit you'd likely never return to the scene of your crime.

Getting caught cheating on a steamboat, however, didn't mean you couldn't return to the waters right away to involve yourself in another of the hundreds of floating card games on offer. Wait long enough and you could even return to the very same vessel from which you were ejected, given the constant turnover of passengers — a much less static crowd than the regulars at a given watering hole.

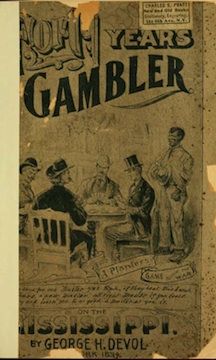

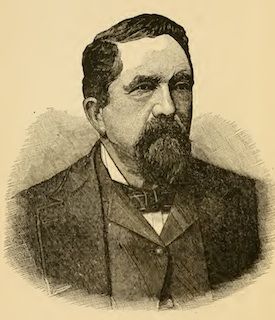

Probably the best known example of such riverboat-riding risk-seekers during the heyday of steamboat poker was George Devol, his reputation made and preserved thanks primarily to his popular and undoubtedly embellished 1887 memoir Forty Years a Gambler on the Mississippi.

"I Felt As If I Were Fixed for Life"

Born in 1829 in Ohio, Devol would spend nearly his entire life in transit, mostly on steamboats, then later on trains on the country's growing railroad lines. In his book Devol shares his life story in roughly chronological fashion via 177 short chapters of three pages or less, each presenting a brief anecdote from his colorful life.

The result somewhat resembles 18th- and 19th-century British bildungsroman or "coming-of-age" novels featuring a central character winding through a serious of episodic adventures and learning various lessons while growing to adulthood. It also establishes a pattern of sorts followed by later "poker memoirs" like Doyle Brunson's The Godfather of Poker and more recently Mike Sexton's Life's a Gamble (reviewed here) — that is, a life presented through a series of gambling stories.

However, unlike Tom Jones or David Copperfield — or Brunson or Sexton, for that matter — Devol's character doesn't evolve all that much throughout his narrative. In fact, he seems to have adopted self-assured philosophy at a very early age, mostly sticking to it throughout the four decades' worth of stories he shares.

A runaway at age 10, Devol finds work as a cabin boy among various steamboats, immediately learning various card games and how to cheat at them. "I learned to play 'seven up' and to 'steal card' so that I could cheat the boys," he explains in an early chapter. "I felt as if I was fixed for life."

He eventually learns other card-based gambling games like "red and black" and three-card monte while remaining mostly on steamboats, working in various capacities for the next seven years. During that time he also discovers other means of cheating including how to "stock a deck." He derives additional income running games of faro, keno, and roulette.

A short stint back home helping his brother caulk steamboats does little to convince him to give up the gambling life. After dramatically dumping his caulking tools in the river, Devol declares his life plan to his brother.

"I told him I intended to live off fools and suckers," Devol writes. "I also said, 'I will make money rain;' and I did come near doing as I said."

George Devol, Gambling Superhero

Poker soon emerges as the game Devol finds most lucrative, whether playing "on the square" or — more often than not — with some ill-gotten edge. With barkeeps and deck hands working as accomplices on seemingly every boat — in addition to the more steady partners with whom Devol worked over the years — the stream of cash flowing into Devol's pockets seems to roll without ceasing, not unlike the Mississippi itself.

Devol's reputation begins preceding him, and somewhere around the early 1860s (in his early thirties) he's already starting to encounter people who either remember him or know his reputation.

The stories fall into a only a few categories that quickly become familiar to the reader through repetition. Many feature the "narrow escape" in which our hero has to jump off moving boats and swim ashore or sneak out amid crowds to avoid being caught and punished by those he's swindled. Others show "the fighting gambler" able to win physical battles following gambling victories, usually landing solid blows after his attackers swing and miss. Then there's the "soft-hearted hero" category featuring Devol returning winnings to "suckers" for whom he feels sorry, including several churchmen.

Representing the latter subgenre is "Lost His Wife's Diamonds" in which Devol wins a few hundred off of a gentleman who leaves and returns with a velvet box full of jewelry. Devol gives him $1,500 for it, then proceeds to win that off of him as well. The next day Devol spots the man with his wife and child, and notices "the lady's eyes were red, as if she had been crying." He has the box full of diamonds delivered to the family's room, benevolently refusing to give the man his address to allow him the chance to pay him back.

Probably the most frequently evoked story type is the "outcheating the cheaters" tale that resembles Twain's short story. For example, in one story titled "He Knew My Hand," a poor gentleman is unaware of who Devol is and approaches him for a ten-cent ante game of poker. "We played along, and I was amused to see him stocking the cards (or at least trying to do so)," says Devol, who lets the fellow successfully cheat him out of a few small pots.

The stakes go up, and eventually Devol is dealt three jacks. By then, however, he's already held out four fives from the deck, and after a series of raises shows his quads at showdown. "'That is not the hand you had,'" objects his opponent, giving away that he'd cheated. "How the d---l do you know what I had?" Devol understandably responds.

"You are a gambler," says the man accusingly as he pulls a knife, the word here appearing as though it were a synonym with "cheater." But Devol raises him, weapon-wise, by drawing "Betsy Jane" — earlier described as "one of the best tarantula pistols in the Southern country" — thereby settling the matter.

"A True Gambler's Word"

Cheating other cheaters is a favored activity for Devol, something that seemingly satisfies an inner sense of justice for him, albeit in a somewhat ironic way.

"When a sucker sees a corner turned up, or a little spot on a card in three-card monte, he does not know that it was done for the purpose of making him think he has the advantage," Devol explains near the end of his book in a chapter titled "General Remarks." Setting up opponents to think they have an unfair edge often forms a central strategy for Devol when he in fact is the one with the advantage.

"It is a good lesson for a dishonest man to be caught by some trick," he affirms, "and I always did like to teach it."

That Devol himself was a dishonest man doesn't seem to suggest any self-contradiction to him, though. Indeed, Devol is entirely content with himself from a moral standpoint, describing a kind of code of honor he has chosen to follow that perhaps sounds familiar.

"A gambler's word is as good as his bond," writes Devol, "and that's more than I can say of many business men who stand very high in a community. I would rather take a true gambler's word than the bond of many business men who are to-day counted worth thousands. The gambler will pay when he has money, which many church members will not."

It's a fine sentiment, although it reads much differently when you remember the designation "gambler" also indicates a willingness to cheat.

The Evolution of Gambling (and Cheating), and of Attitudes Towards Both

This definition of a "gambler" as both a risk-taker and a morally dubious individual for whom cheating is just "part of the game" would stick well into the 20th century, only fading somewhat by the century's latter decades. That's not to say cheating would disappear from poker entirely, but the likelihood of a cheater standing up proudly like Devol to narrate all of his successful swindles diminished markedly.

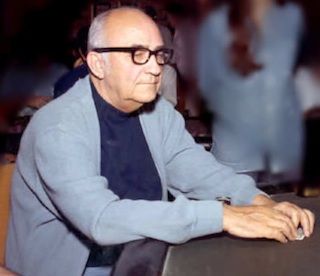

To explore an example, in 1975 the journalist Jon Bradshaw published a collection of profiles of people who in a variety of contexts had achieved success as gamblers, titled Fast Company: How Six Master Gamblers Defy the Odds — And Always Win. One of those featured in the book is the venerable Texas gambler Johnny Moss, who after many years "fading the white line" culminated a lengthy, adventurous career in poker with three early World Series of Poker Main Event titles and 10 WSOP bracelets.

Bradshaw explores with Moss the subject of what it means to be a "professional gambler." Unlike Twain's Backus or George Devol, Moss takes a different tack with his definition. In fact, rather than make a willingness to cheat part of what makes a gambler a gambler, Moss suggests cheating disqualifies a person from rightly assuming the title.

"I'm a respectable gambling man," Moss tells Bradshaw, speaking to him at the 1973 World Series of Poker. "I ain't never cheated, ain't never connived," he adds.

He tells of being a teenager, and like Devol learning how to cheat at cards and dice early on from a group he describes as "fast company" (giving Bradshaw the title of his book). However, the lesson Moss took away — so he says — was not in how to cheat himself, but how to defend himself against those who might try to cheat him.

"To be a professional gambler," says Moss, "you have to know how to play all them games," referring to the many variants of poker being played at Binion's Horseshoe Casino in the events of the 1973 WSOP. "You [also] have to keep your eyes open for two dangers, the hijackers and the law," he adds, noting that a "professional" knows how to "duck and dive" when necessary, since the life is like "livin' in the jungle."

Moss later more specifically describes "three classes of gamblers" to Bradshaw — "cheaters, cheating gamblers, and professional gamblers."

"Now, if a cheater can't cheat, he won't play. He just won't set down less'n he's got something agoin'," says Moss. "If a cheating gambler can't cheat, he'll play, but they can't win when they have to play, and a professional gambler winds up with all the money. The boys playin' in here, they're professionals."

In other words, being a successful cheater is hardly a badge of honor in such a system. In fact, according to Moss, to cheat is to deny oneself the title of "professional gambler."

What's interesting, of course, is how Moss presents his story to Bradshaw in a highly-edited form. According to Doyle Brunson in The Godfather of Poker, Moss had once been forced to leave Las Vegas because of his cheating at cards, barely escaping with his life after being caught doing so by mobsters. He and Moss would become friends later on in Texas during Brunson's own rambling, gambling years on the road. "But the one thing I didn't like about him was his tendency to cheat," says Brunson of Moss.

Brunson adds, importantly, that even though "Johnny was not one to give honesty an edge," attitudes toward cheating were different back when Moss was more likely to do it than to preach against it. "In those earlier days, in the forties and fifties, it was almost acceptable," says Brunson.

Conclusion

What wasn't acceptable even then, nor in the 1970s or today, was to champion one's own cheating. Moss's selective presentation of himself to Bradshaw proves as much.

But as Devol tells it — and with glee — back in the late 19th century it was a different story. In Forty Years a Gambler, he's also obviously presenting a certain, edited version of himself, omitting or changing details in order to present his story in the most favorable way.

But rather than minimize or hide his cheating, Devol celebrates it as a highlight.

He is, after all, a professional gambler.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America’s Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.

Images: From George Devol, "Forty Years a Gambler on the Mississippi," 1894 edition, public domain; "Johnny Moss at the 1974 World Series of Poker," Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 3.0 Unported.

Want to stay atop all the latest in the poker world? If so, make sure to get PokerNews updates on your social media outlets. Follow us on Twitter and find us on both Facebook and Google+!