Practice Active Learning When Off the Felt

There’s an excellent, classic instructional book for golfers by the great Ben Hogan (with Herbert Warren Wind) called Five Lessons: The Modern Fundamentals of Golf. It’s short, elegantly illustrated, and very clear. I suspect any golfer, of any skill level, would benefit from reading it.

Of course, you don’t have to play golf to see the challenge such a book presents. You could read Five Lessons a dozen times — heck, you could even memorize the thing — and be no closer to achieving a perfect swing than the newest of newbies. If you want to learn golf, you have to pair reading with doing.

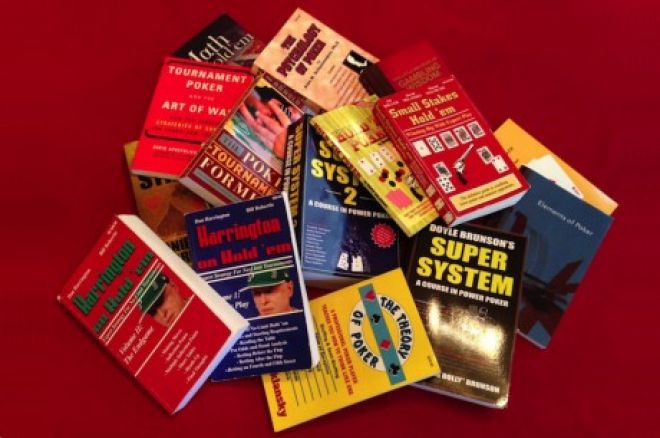

So it is with poker books and poker. The best of the strategy books, from the classic Super/System by Doyle Brunson and his justly famous collaborators to the latest offerings from Two Plus Two, can be extremely sound investments. But you can’t just read them and automatically expect to maximize your ROI.

You have to read them actively. You have to engage with the material, and translate the words on the page into action at the table. That’s active learning, and it’s not that different from reading about proper technique for your golf swing and putting that knowledge to work at the range.

What does active reading look like? Wrong question. What does active reading feel like? At the risk of alienating everyone who hated school, active reading feels like doing homework. (But in the case of poker, it’ll be homework you love, right?)

When you read actively, you highlight passages and make notes. You rephrase concepts in your own words. You try to relate what’s on the page to situations or player types you recognize. You underscore bits that strike you as opaque, so you can return to them or ask a poker friend about them. You work through the math by hand, just to get it in your brain. You quiz yourself.

If you think about it, that’s exactly how you mastered material for, say, a history final. You engaged different parts of your brain with the content both to ensure you knew it and to ensure you could deliver that content back to your teacher.

But for poker, mastery means two added elements: You must be able to extrapolate general principles from specific examples, and you must be able to turn theoretical concepts into the basis for action.

Take a book like David Sklansky’s The Theory of Poker. As its name suggests, this book isn’t about the play of specific hands, but rather provides a foundation for your understanding of the game in the broadest sense. It will take some real thinking to put Sklansky's ideas into play.

On the other hand, Dan Harrington’s tournament poker books — Harrington on Hold'em: Expert Strategy for No-Limit Tournaments — are almost entirely based on specific situations and hands. You might encounter very similar situations in your own play, but the challenge with those books is to learn to think like Harrington, and apply that thought process to your own game. (He gives you an excellent opportunity to try it, by the way, in Volume III: The Workbook.)

My approach to reading poker books actively really does feel a lot like challenging homework. I like to read a book through once, almost hurriedly, marking sections that I don’t understand or I know I need to work on in real life. Then I’ll reread more carefully, taking copious notes, and creating lists of tactics, strategies, or situations I'm eager (or at least willing) to try.

But don’t try to apply all your newfound learning at once. Give yourself a limited range of “assignments” and focus on looking for opportunities to use them.

I might, for example, pick two or three concepts — ones that are new to me or simply ones I’m not good at — and write them out in a small notebook before a session. The list might include items like “Three-bet more in position” or “Protect my weak hands” or “Raise on the come.” I consider writing these concepts in longhand a key component of active learning. I rarely forget things I’ve written out, and often forget things I’ve typed or cut-and-pasted. I’ll often add really obvious things to that list as little aide-mémoires, too, such as “Look left before acting” or “Position is everything.”

Poker books, and perhaps to an even greater extent, poker videos, can teach you how to improve your game, but that’s not the only reason to study them. You strive to master theoretical and instructional material because it helps you understand what other players are doing — a huge source of advantage if you are good at recognizing what you see on the table and can devise strategies to counter it.

Poker strategies evolve at an almost ridiculous pace, but the good old-fashioned poker book still has its place on your shelf (or on your tablet). And by actively engaging with this material — along with videos, forums, and discussing situations with friends — you’ll surely elevate your game a notch or two.

So release your inner nerd, grab that highlighter and a yellow pad, and get to work on your game!

Get all the latest PokerNews updates on your social media outlets. Follow us on Twitter and find us on both Facebook and Google+!