The Postle Lawsuit is Not as Clear Cut As It May Seem

Do you know any poker players who think Mike Postle is innocent?

Juries hesitate to assign blame based solely on circumstantial evidence.

Me neither. It is hard to imagine any seasoned player who has watched the Joey Ingram and Doug Polk videos on Postle concluding otherwise.

But the recently filed Federal lawsuit against Postle and Stones Gambling Hall may not be as clear cut as many poker players think. Postle may prevail, even if he did cheat. That result may seem absurd to the poker community, but it is a function of the various ways the legal system protects people from false accusations.

- First, the burden of proof is on the plaintiffs. Postle could offer no defense whatsoever and still win.

- Second, the plaintiffs must meet the preponderance of the evidence standard, meaning they must prove their case is more likely to be true than false. This standard is easier to satisfy than the beyond a reasonable doubt standard that applies in criminal cases, but it still presents a high bar.

Third, the jury system is all about variance. Jurors space out. They fall asleep. They may not understand the issues or the evidence. Jurors who may not know the difference between a spade and a heart may struggle to grasp ranges, removal, and reverse implied odds. They may not be too good at statistical analysis either.

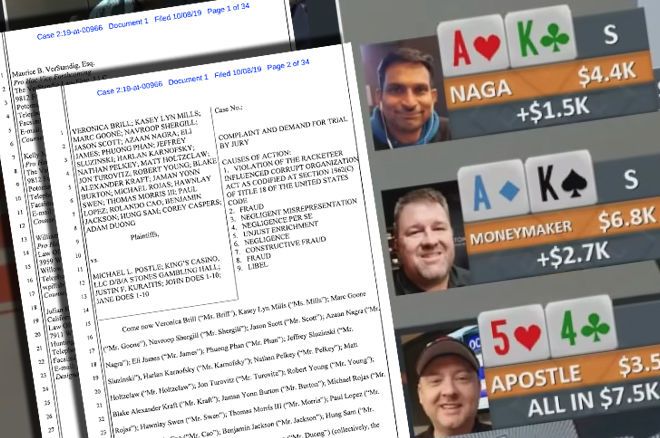

Attorney Maurice VerStandig has drafted a very good complaint on behalf of the plaintiffs, but he has his work cut out for him convincing a jury of poker neophytes that average win rates of sixty big blinds per hour and calling two all-ins with five-four offsuit are conclusive evidence of cheating, upon which millions of dollars in damages should be awarded.

- Fourth, the plaintiffs lack something crucial: direct evidence of wrongdoing. New facts may emerge as discovery progresses, but to date, no so-called smoking gun has come to light, such as a confession by a co-conspirator or a phone containing RFID data that links Postle to the livestream’s control room. Juries hesitate to assign blame based solely on circumstantial evidence.

“Expert Testimony”

Absent a smoking gun, the plaintiffs’ case is essentially reduced to expert testimony and statistics. “Expert testimony” means a top poker pro testifying under oath on behalf of the plaintiffs—basically the Ingram and Polk videos being re-enacted in court.

But expert testimony and statistics can boomerang on plaintiffs. Statistical arguments are subtle and complex. Juries may bristle if they feel like a rich, arrogant poker pro or a mathematics professor is essentially telling them, “Trust us smart people.” If the experts are paid (even if only their costs are reimbursed,) that can look bad. The defense will call its own expert witnesses, who will contradict everything the plaintiffs’ experts say. And plaintiffs’ expert testimony can be turned against them during cross-examination. Let’s consider some possibilities:

He’s Winning More Than Sixty Big Blinds an Hour

The issue here is sample size. The complaint alleges Postle participated in sixty-eight streams, and the average length of those streams was reportedly 2-3 hours. So let us assume 170 hours of streamed play—not a huge sample given that pros usually calculate their win rates over thousands of hours. If we were randomly to choose a smaller sample, a pro’s hourly win rate could be much higher.

Now imagine the cross-examination of plaintiffs’ expert witness: “Have you ever been on a heater? Can your hourly win rate be much, much higher than usual during a heater? Can heaters last a long time? Can they last several months? And over several months, is it normal for a poker pro to exceed 170 hours of play?”

These arguments may sound specious to pros while raising doubts in juror minds.

Postle Played and Won With Really Bad Hands

Here, the defense simply asks whether decent players ever play bad hands. Live reads, boredom, tilt, drunkenness, wanting to gamble, defending straddles—the list of reasons for playing bad hands is long. In fact, occasionally playing weaker cards is a bedrock of GTO strategy, i.e. balancing ranges.

How to defend a play like calling two all-ins with five-four offsuit? Out of the hundreds of hands over those 68 sessions, Postle’s critics have cherry-picked a few examples where Postle both played bad hands and got very lucky. Postle’s lawyers will in turn cherry-pick other hands from the stream showing Postle playing proper ranges. They will also highlight fishy play on the stream by Postle’s loose aggressive opponents, arguing that Postle was far from an outlier.

They will also highlight fishy play on the stream by Postle’s loose aggressive opponents, arguing that Postle was far from an outlier.

He’d Have to See the Hole Cards to Play This Way

A key charge against Postle is that he is making unique plays that no player would make unless he could see his opponents’ hole cards. In response, the defense will show the jury video after video from YouTube of players (including, possibly, some of Postle’s opponents on the Stones stream) making hero calls, hero folds, sick reads, bluffs with air and other unconventional plays. As those cherry-picked videos of Postle making unorthodox plays start to look less unorthodox, jurors will be left with a choice between the opinion of an expert and their own eyes.

Plaintiffs’ response: “Okay, other pros sometimes make these plays, but he’s doing it way more often.”

Postle’s lawyer: “How do we know that? Has someone tracked the statistical prevalence of hero calls, hero folds, and bluffs with air in poker globally over the past decade? And is there an official governing body in poker that certifies what lines are proper to take in a given situation?”

He Only Plays on the Stream

Rule #1 of game selection—play at action tables where you are more skilled than your competition. Like any good player, Postle was focusing his fire on the best spots. The games reportedly got really good when the stream started and tightened up when the stream ended. So why stick around after the stream? Many have asked why Postle did not play higher stakes on Live at The Bike or in Vegas, but why leave behind a great game to go play in a tougher game?

He’s Cheating Right There on TV

If he were cheating on a livestream, wouldn’t he try to conceal it, perhaps by intentionally losing more often? Why be so conspicuous?

He’s Constantly Looking at his Phone

We often see Postle looking down, but, pending release of more video from more camera angles, we usually do not actually see his phone on his lap or in his hand while he is looking down.

Back to the cross-examination: “Do players ever look at their phones at the table? Have you ever looked at your phone? Is this common behaviour? What about casinos where players are not allowed to use their phone during a hand—do players sometimes break this rule? Have you ever broken that rule?”

And by the way, where is the evidence linking Postle’s phone to the stream’s control room?

The Graphics Changed in the Middle of Some Big Pots

“Interesting. You’ll have to ask the Stones IT team about that. My client was out on the floor.”

He Had a Bulge in His Hat

“Your honor, I’d like to introduce into evidence hundred recently purchased new and used hats of various brands, styles, and sizes displaying bumps, creases, and other irregularities.”

“He Didn’t Cheat, But if he Did Cheat, It Wasn’t a Problem”

Lawyers also do something called arguing in the alternative: “He didn’t cheat, but if he did cheat, it wasn’t a problem.” This kind of defense is risky because it can seem hypocritical to non-lawyers, including jurors. But two arguments along these lines may crop up. They do not need to be fully developed to raise doubt in jurors’ minds, just hinted at:

The “Everyone Cheats” Defense

Collusion and angleshooting are widely frowned upon yet not uncommon, while very hard to prove. Policies are inconsistently enforced. It is rare that a player is blacklisted from a property. Rarer still is a suspect hand declared null and void. Yet players play. They take on board the risk that other players may cheat and try to adjust their play to counteract it. In effect, cheating is just part of the game.

To which a seasoned player responds, “C’mon, accessing hole cards is way, way over the line.” But a juror who knows nothing about poker, who still thinks of poker as a sleazy game played in back rooms, may start to think of Postle as just a shark among sharks.

His lawyers can portray him as a skilled “feel” player on a heater being unfairly targeted by sore losers on extended tilt and YouTubers looking for hits.

The “Reality TV” Defense

The stream was stage-managed to create drama to boost YouTube views. Everyone was directly or indirectly in on it. That is why variance was so much higher during the stream. And like any reality TV show, the stream needed a villain.

Stones is also a defendant, presumably because Stones has deep pockets. The complaint never alleges that Stones or its employees were aware of cheating. The key allegations are that Stones did a bad job investigating the allegations against Postle and wrongly assured players that there was no cheating.

To make a strong case against Stones, the plaintiffs will effectively need to prove Postle was in fact cheating—a big if. Stones will also argue that they had reasonable safeguards in place, that their investigation was conducted professionally, and that it turned up no wrongdoing. What was Stones supposed to tell players, “Our investigation found no evidence of cheating, but please exercise extreme caution when playing at our casino”? Moreover, casinos will always argue they are not liable when players on property cheat or rob other players. If casinos had to indemnify every victim of a scam or robbery on their gaming floors, they could not afford to insure their operations.

Finally, Postle, who is accustomed to TV cameras, may turn out to be a compelling and sympathetic witness—a regular guy who the entire poker world suddenly ganged up on. His lawyers can portray him as a skilled “feel” player on a heater being unfairly targeted by sore losers on extended tilt and YouTubers looking for hits.

In fact, if I were Postle’s lawyer, I would start my opening remarks with: “Ladies and Gentlemen of the jury, this lawsuit is the most extreme example of tilt in poker history.”

Except the jurors won’t know what “tilt” means.

Joshua M. Zimmerman is a lawyer admitted in New York and Hong Kong who spent twenty years executing corporate and sovereign financings throughout Asia. He is a graduate of Princeton and the University of Chicago law school and is ranked #67 on Hendon's Hong Kong all-time money list.

In this Series

- 1 Mike Postle Accused of Cheating During Livestreamed Cash Games

- 2 10 Suspicious Hands Played by Mike Postle on Livestream

- 3 Stones Gambling Hall Suspends All Poker Broadcasts Following Alleged Cheating

- 4 Stones Launches Investigation Into Postle Cheating Saga

- 5 PokerNews Podcast: Stones Scandal

- 6 Mike Postle Goes on Mike Matusow's 'The Mouthpiece' Podcast, Denies Cheating

- 7 LATB, WSOP, PokerStars, and More on Security of Their Livestreams

- 8 Mike Postle, Stones Parties Hit With $10M Lawsuit

- 9 Graphics Company Reacts to Mike Postle Cheating Allegations Saga

- 10 Watch List: Investigative Videos Mike Postle Cheating Allegations

- 11 Watch Whistleblower Veronica Brill on Joey Ingram's Podcast

- 12 PokerNews Podcast: Jeff Boski on Postle Scandal

- 13 Mike Postle's Lawyer: "I Know Such Streaks Are Possible"

- 14 The Postle Lawsuit is Not as Clear Cut As It May Seem

- 15 Top 10 Stories of 2019: Mike Postle Caught Cheating on Livestream

- 16 Mike Postle Accused of Avoiding Court Summons

- 17 Mike Postle Files, Possibly Leaks Own Motion to Dismiss

- 18 Marle Cordeiro Files Lawsuit Against Mike Postle Seeking $250K

- 19 Stones in New Motion to Dismiss Mike Postle Lawsuit: “Casinos Do Not Owe a General Duty of Care to Gamblers"

- 20 Motion for Sanctions Filed Against Mike Postle; Latest on Motion to Dismiss

- 21 Plaintiffs Respond to Stones & Justin Kuraitis Motions to Dismiss in Mike Postle Case

- 22 PokerNews-Op Ed: Postle Tightlipped in Oral Arguments, Motion to Dismiss Outcome a Coinflip

- 23 Plaintiffs' Case Against Mike Postle, Stones Dismissed by Judge

- 24 Plaintiff's Lawyer Offers a Reflection on the Stones/Mike Postle Ruling

- 25 Judge Dismisses Marle Cordeiro’s Case Against Mike Postle for Lack of Jurisdiction

- 26 Settlement Finalized for 60 Plaintiffs in Case With Stones, Kuraitis

- 27 Mike Postle, Justin Kuraitis Break Silences in Wake of Settlement

- 28 Leaked Term Sheet Reveals Details Regarding Stones/Kuraitis Settlement; Plaintiffs Paid $40,000

- 29 The Muck: Kuraitis, Stones Lash Out After Twitter Silence

- 30 Plaintiff's Counsel Maurice "Mac" VerStandig Reflects on the Mike Postle Litigation

- 31 Galfond, Berkey Helping Propel Research into Mike Postle's Play

- 32 Top Stories of 2020, #5: Mike Postle Saga Winds Down

- 33 Postle Hit With Two Motions to Strike, Dropped by Lawyers