Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America’s Favorite Card Game

It's a Saturday afternoon in 1944. You've wandered into the local movie theater for a few hours of entertainment, hoping perhaps to miss the newsreels covering recent battles in Europe or attacks in the Pacific in favor of some lighter fare. Or say it's last week, and after a spin through the dial you've paused on one of the classic film networks, again seeking something less dispiriting than what's streaming from the news channels 24-7.

You happen on an already-begun western, Tall in the Saddle starring John Wayne. Such might well have occurred during the 1940s when arrivals and departures of movie patrons didn't strictly adhere to films' scheduled show times. So, too, might it happen today in our otherwise on-demand world, with the sight of the Duke entering an older gentleman's office temporarily halting your remote button-pushing progress.

"Mr. Rocklin," begins the older fellow who squints uncertainly through a pair of round bifocals. "What happened between you and my stepson last night?" he asks with a quizzical look.

Cut to Wayne — that is, Mr. Rocklin — who hesitates just a moment as if considering the best way to answer. Then, with an earnest look, he does.

"Poker," he says.

"Oh," comes the nodding response, and the pair and plot move on.

Nothing more needs to be said. The audience nods as well, then and now. We all know poker, after all, whether we happen to play America's favorite card game or not. Don't we?

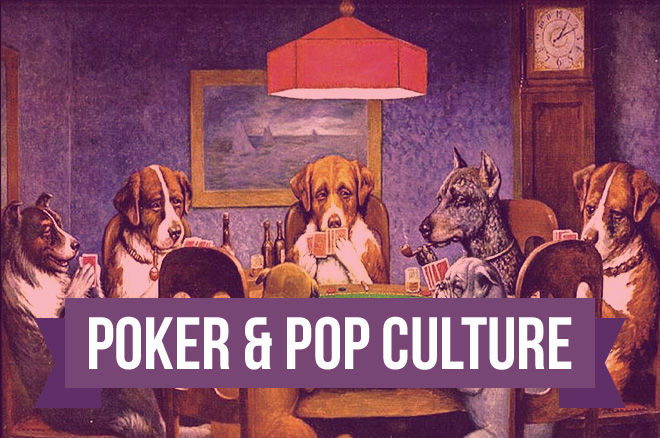

We know poker as a game played by cowboys and card sharps, by soldiers and scouts, by presidents, peasants, and painted dogs. We know that unlike hearts or euchre or crazy eights, poker often requires players to match not just cards and wits, but egos and nerve as well. It's a game in which the competition can be intellectual, emotional, mental, psychological, analytical, verbal, and — as appears might have been the case with Rocklin and the elderly gentleman's stepson the night before — even physical.

It's a game that suits the familiar image of the Old West cowboy Wayne is portraying, a figure of rugged independence who commands respect, who instinctively understands the relationship between risk and reward, and who never shies from conflict. It's also a game befitting of the image of America itself, the country in which poker originated and for which the mythic cowboy — part real, part imagined — also stands as an emblem.

In other words, when Wayne says "poker," you don't have to be a player yourself to have an idea what he means. You don't even need to know the rules in order to understand the game's logical place in a story such as this. A game of cards would provide a ready context for characters to clash, given how poker occupied a prominent place in the culture during the time of the Old West. Or during the 1940s, for that matter. Or today.

But step back a moment. Poker? Sure, we know poker. But how well?

I'm not just referring to the way flushes beat straights and sharks devour fish, but to all of those stories and episodes — the real-life ones, those that are made up, and the many combining what's true and what's imagined — that have helped make the game seem so familiar to so many.

How much do we know about poker, really?

The "Unpardonably Neglected" Game?

Here's the deal.

This series of columns starts with a premise. While most of us (especially among the poker-playing part of the population) are well aware the game has played a prominent role in history and culture, especially in America, a lot of the details of that narrative may not be so well known or understood. Furthermore, even those stories and anecdotes that are thought to be "common knowledge" and have been often passed around as the game's enduring lore are often only known partially, with contexts missing and/or distinctions between fact and fiction disregarded.

That's not to say the story of poker has been ignored. Just that there are facets of that story that perhaps deserve closer attention.

Speaking of poker deserving greater scrutiny, you've probably heard before American author Mark Twain's famous quote about poker being "unpardonably neglected." Here's what the author of Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn, and many other books and stories — including a few about gambling on cards — once said about the game's place in American culture:

There are few things that are so unpardonably neglected in our country as poker. The upper class knows very little about it. Now and then you find ambassadors who have sort of a general knowledge of the game, but the ignorance of the people is fearful. Why, I have known clergymen, good men, kind-hearted, liberal, sincere, and all that, who did not know the meaning of a 'flush.' It is enough to make one ashamed of one's species.

The quote gets passed around a lot, although almost always without much reference to the context in which it appeared. In fact, a little bit of digging shows that Twain never actually wrote these words but rather delivered them from a stage.

In 1876, Twain collaborated with Bret Harte — another fiction writer who later would pen a famous poker-related story, "The Outcasts of Poker Flat" — to write a four-act comedy based on a character Harte had created some years before. The play was produced in New York a year later, and it was at that performance Twain delivered a short, humorous speech discussing some of the scenes. Referring to one episode occurring near the end of the first act, Twain joked that "for the instruction of the young we... have introduced a game of poker."

It's at that point Twain launched into his seeming lament about poker's neglect. However, besides overlooking the context, those quoting the passage often also skip over the possibility that the satirist Twain — himself a poker player — was actually bluffing.

Very often you'll see the observation repeated as a straightforward complaint about poker's lack of cultural notice. Yet Twain's audience would have been well aware that poker was hardly neglected, understanding right away that his admonishment of the nation's wealthy, the politically powerful, and its spiritual leaders was no doubt delivered with tongue firmly in cheek. In truth, all three of the groups mentioned by Twain were certainly well represented at the late 19th-century tables.

Stephen Crane's short story "A Poker Game" — written not too much later though not published until the start of the next century — presents a hotel room game between a moneyed real estate maven and young heir to millions as entirely customary, with poker described as having by then become "one of the most exciting and absorbing occupations known to intelligent American manhood." Such a scene is reflected further by Cassius M. Coolidge's contemporaneous "Dogs Playing Poker" series of paintings which likewise suggest in a less sober way poker to be a favorite pastime of the middle-to-upper class.

Ample evidence shows the nation's elected officials were also avid players in Twain's day. In Jack Pots. Stories of the Great American Game (published in 1900), Eugene Edwards declares that by the end of the 19th century "Washington is popularly regarded as the great poker center of the United States" in large part because "when Congress is in session, the whole town is in a fever of excitement, and the easiest way to work off the surplus steam is with a pack of cards." Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant had both been poker players, and just a few years before Twain's comment an ex-Congressman, Robert C. Schenck, had compiled a book of rules for draw poker sometimes regarded as among the first of its kind. At the time, Schenck literally was an ambassador, serving in London in Grant's administration as Minister to the United Kingdom.

The clergy, too, are frequently described taking seats at poker tales of the period. Of that group Rev. Thankful Smith of Henry Guy Carleton's Thompson Street Poker Club stories from Twain's era serves as a representative example. When challenged by an opponent that his aggressive raise of a hand isn't in "de speret ob de Gospil," the good reverend immodestly fires back "'Dis haint no prar meetin'." Twain himself had earlier written a short story titled "Science vs. Luck" in which a group of churchmen play a poker-like card game in order to help determine a legal question over whether the game constituted gambling.

No, poker hasn't been neglected. Not then, and not today. But even this small sample of anecdotes and tales suggests there's probably more to poker's story — a lot more — than some might realize.

Poker in Popular Culture: One Long-Running Bluff

The historian John Lukacs once described poker as a game of chance in which "it is not so much fate as human beings who decide" how the game is played. In other words, in poker (says Lukacs), "the important thing is not what happened but what people think happens."

The same might be said for the stories that get told about the game afterwards.

Poker is game that requires the blurring of fact and fiction. After all, every single hand of poker that has ever been played has featured a combination of the known and unknown, with the distinction between the two purposely complicated by the efforts of everyone involved to hide or misrepresent details regarding what is and what is not.

Like so many unreliable and contradictory eyewitnesses at a crime scene, players sitting at the same table witnessing the same hand often will relate what happened in that hand differently. Omissions and embellishments often compromise the veracity of even the most straightforward chronicle of a hand or session as conflicting accounts of what took place exhibit Rashomon-like contradictions and hopelessly blinkered subjectivity. That means the truth of so-called "nonfictional" accounts of poker appearing in letters, memoirs, biographies, articles, guide books, and elsewhere is sometimes — perhaps often — suspect.

Meanwhile, fictional representations of poker involve creative enhancements, too. And those versions of the game — such as appear in songs, paintings, radio programs, films, television shows, stories, and novels describing poker and its players — have also helped influence what many think they know about poker. They have even affected how the game has been played over the decades, whether on steamboats and trains, in saloons and gambling dens, on military bases and encampments, or in card rooms, casinos, and private homes.

You might say the story of poker as has been told in popular culture — in both history and fiction — is itself one long-running bluff.

In these columns, we'll be presenting a detailed consideration of poker's history and its place within popular culture, in particular American popular culture. By looking at the game's origins, development, and growth into a favorite pastime of millions, we'll do what we can to sort facts from fictions, acknowledging here at the start that in many cases and with many of poker's most notorious stories and characters, the "cards aren't on the table" in full view to prove unambiguously what has taken place.

But we've wandered into the story in the middle. Starting next week, we'll back up to the beginning — even before the first hands of poker were ever dealt — as we together try to figure out "what happened" (or what people thought happened) when it comes to the story of poker.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America’s Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.

Want to stay atop all the latest in the poker world? If so, make sure to get PokerNews updates on your social media outlets. Follow us on Twitter and find us on both Facebook and Google+!