Poker & Pop Culture: Bret Harte's "The Outcasts of Poker Flat"

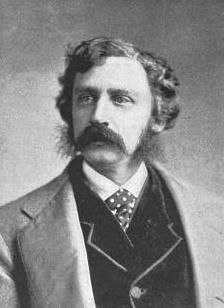

One of the more enduring cultural reflections on 19th-century poker is the short story "The Outcasts of Poker Flat" by the American poet and fiction writer Bret Harte. First appearing in the California-based magazine Overland Monthly in January 1869, the story helped make Harte famous and was later the basis for several films and an even an opera.

Rather than depict a poker game or exploit the inherent drama produced by the conflict of a poker hand, Harte's story instead uses poker in a thematic way, presenting the game as one of several activities deemed morally objectionable and deserving of punishment by those with authority in a mid-century California town. Ultimately the story presents a thoughtful sketch of the Old West that conveys the complicated status of poker in American culture at the time it was written (and that resonates still today).

Getting Rid of Poker Players and Other "Improper Persons"

The story opens in late November 1850 in the interestingly named California town of Poker Flat. John Oakhurst, a professional gambler, correctly senses a sudden alteration in the town's "moral atmosphere" thanks to the strange behavior of others in his presence. Sure enough, in a "spasm of virtuous reaction," a secret committee has been formed "to rid the town of all improper persons," Oakhurst included.

Two men have already been hanged, and soon Oakhurst and three others — a thief known as "Uncle Billy" and two prostitutes, "Mother Shipton" (a madam) and the "Duchess" — are forcibly exiled from Poker Flat.

The narrator highlights the committee's hypocrisy, noting how some of those in charge of executing such justice had lost to Oakhurst at poker. In fact, we're told he probably would have been hanged as well if not for "the crude sentiment of equity residing in the breasts of those who had been fortunate enough to win from Mr. Oakhurst."

Oakhurst is described as receiving his punishment with "philosophic calmness."

"He was too much of a gambler not to accept fate," we are told. It is this recognition of that which he cannot control Oakhurst has learned at the tables, a character trait that surfaces again at the story's conclusion.

A "Streak of Bad Luck" for the Outcasts

We follow the four outcasts out of town as they travel toward neighboring Sandy Bar, a trek that requires a difficult passage through the Sierras. The trip could be accomplished in a day, but after traversing half its length the group attempt to persuade Oakhurst into stopping and setting up camp for the night.

Using a poker metaphor, Oakhurst argues against their "throwing up their hand before the game was played out." But ultimately he gives in and they set up camp.

While the others get drunk, a young man named Tom Simson happens on the group, accompanied by his girl, Piney. The pair are traveling in the opposite direction, leaving Sandy Bar for Poker Flat in the hopes of getting married starting a new life there.

Oakhurst knows Simson from having played poker with him before at Sandy Bar. In fact, Oakhurst cleaned out the youngster — referred to in the story as the "Innocent" — then afterwards gave him back the money he'd won, instructing him never to gamble again. For this gesture Simson remains grateful. It also shows Oakhurst is hardly as malevolent or dangerous as the Poker Flat committee judged him to be.

Oakhurst again agrees to help Simson by arranging to allow him and Piney to camp with the others. The skies — and the story — take a dark turn, however, as they awake the next day to discover a snowstorm. And making matters worse, Uncle Billy has stolen off with the mules, leaving the remaining five no method of escape.

Only possessed with ten days' worth of provisions, Oakhurst recognizes the situation as potentially dire, but keeps his concern to himself so as not to worry the others.

They pass the time singing and listening to Simson retell stories from Homer's Iliad, translating them into "the current vernacular of Sandy Bar." Meanwhile, Oakhurst is careful not to produce the pack of cards he carries with him, the implication being he doesn't want to introduce poker into this scene of "square fun."

That said, poker has prepared Oakhurst well for the present trial. Long sessions have meant he's "often been a week without sleep," thus preparing him to handle the test of physical endurance the trip has presented. Poker has also helped equip Oakhurst with a kind of mental fortitude to withstand the sudden misfortune that has befallen the travelers.

"Luck... is a mighty queer thing," he tells Simson. "All you know about it for certain is that it's bound to change. And it's finding out when it's going to change that makes you."

He additionally notes the "streak of bad luck since we left Poker Flat" and how Simson has now been made to share in it. However, after a lifetime of riding out such downswings in fortune, Oakhurst soon comes to realize this to be one instance in which his luck will not changing.

Oakhurst Plays His Last Card

They reach the end of their provisions, and Mother Shipton — who, it is discovered, has been starving herself to save food for the others — perishes. It's yet another example of selflessness among the outcasts, among whom only Uncle Billy shows himself to be morally lacking.

Oakhurst then takes Simson aside, provides him with a pair of snow shoes, then points him in the direction of the town where he and the others cannot go — Poker Flat. When the "Innocent" asks Oakhurst what he intends to do, the answer is brief and to the point.

"I'll stay here."

Alas, although we never learn of young Simson's fate, his attempt to rescue the others fails as the final scene shows "the law of Poker Flat" discovering the Duchess and Piney having died.

"You could scarcely have told, from the equal peace that dwelt upon them, which was she that had sinned," the narrator observes, an implicit criticism of the unfair moral judgment cast upon the outcasts.

The group also find Oakhurst "with a derringer by his side and a bullet in his heart," having shortened his own life by an extra day or two in the hopes of extending those of the others. Before killing himself, Oakhurst had pinned a playing card to a pine tree with his bowie knife, his choice of the deuce of clubs perhaps symbolizing the decreased value he'd estimated his remaining moments to possess.

On the card, the lawmen see that Oakhurst has written his own epitaph: "BENEATH THIS TREE LIES THE BODY OF JOHN OAKHURST, WHO STRUCK A STREAK OF BAD LUCK ON THE 23D OF NOVEMBER, 1850 AND HANDED IN HIS CHECKS ON THE 7TH DECEMBER, 1850."

Understanding the Gamble That Is Life

The story ends enigmatically with the narrator referring to Oakhurst as "at once the strongest and yet the weakest of the outcasts of Poker Flat," although such a paradoxical character assessment can be explained.

What distinguishes Oakhurst — or makes him the "strongest" — is his correct understanding of the way poker requires one to accept the influence of luck, both good and bad. In other words, as he understands it, poker is not an immoral game for "improper persons," but an activity for mature adults able to accept and withstand the game's inevitable ups and downs.

Such is life, of course, with the death-causing snowstorm revealing the cruel indifference of Nature (or "fate") that Oakhurst also accepts with "philosophic calmness."

That said, poker isn't for everyone. Young Simson — the "Innocent" — isn't prepared for its challenge, something Oakhurst recognized after playing with him back at Sandy Bar. Nor are those committee members whose response to losing at cards is to punish winners with execution or exile, and to group poker with other activities thought to violate their self-righteous (and inauthentic) sense of virtue.

Meanwhile, Oakhurst is the "weakest" of the outcasts for the same reason, his understanding of the situation having encouraged his noble self-sacrifice. And it is worth noting that poker has prepared him to accept losing — to know when it is time to have "handed in his checks."

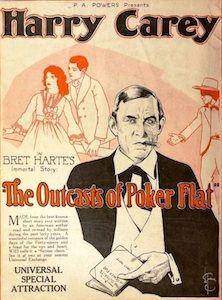

Adaptations

The first adaptation of Harte's story was a 1919 silent film (now lost) starring Harry Carey. It featured an interesting narrative frame in which Carey's character, an owner of a gambling hall, reads Harte's story which then gets dramatized on screen with the owner imagining himself in the role of Oakhurst. When Harte's story ends, the film returns to the gambling hall owner's situation, showing him applying a lesson of sorts from the story to his own life.

A later 1937 version stars Preston Sturges as Oakhurst and like the earlier film adds a considerable number of subplots and additional characters to round out the story. Meanwhile the 1952 adaptation in which Dale Robertson portrays Oakhurst is more faithful to the source, although introduces a villain who in fact plays poker with Oakhurst at one point. That version also features a different ending that finds Oakhurst, the Duchess, and the young couple all surviving.

It was adapted again in 1958 for television with George C. Scott as Oakhurst and a young Larry Hagman as Tom. Then later an Italian film made in 1975 with the (translated) title Four of the Apocalypse also loosely adapted the "Poker Flat" tale, combining it with another Bret Harte story while adding in new material. The "spaghetti western" was directed by Lucio Fulci, best known for gory exploitation fare like Zombi and City of the Living Dead, and thus unsurprisingly contains a lot more graphic violence than Harte's story suggests.

Then just a few years ago (2009-10) the composer Andrew E. Simpson wrote a one-act chamber opera dramatizing the story. It was performed most recently in 2012 (to positive reviews), and from the summary appears to follow the source material much more closely than any of the cinematic adaptations.

Conclusion

"The Outcasts of Poker Flat" neither champions nor condemns poker, but rather evokes the game to suggest certain ideas about human nature and our relative willingness and/or ability to withstand misfortune. It also uses society's judgments about poker as a starting point for exploring our ideas of "good" and "bad" behavior, including the tendency to judge others a lot more harshly than we do ourselves.

Finally, there's something curious about Harte having chosen to include "poker" in the name of the California town from which a poker player is banished and where the game is associated with other activities (thievery, prostitution) deemed "improper." It almost seems like the people of Poker Flat are denying something essential about themselves when trying to rid the town of the game — or at least the town's best player.

In any event, the title of the original story — repeated in most of those adaptations — has an additional effect of associating poker with outcasts, making it seem something belonging to the periphery at best, if not cast out altogether.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America’s Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.

Be sure to complete your PokerNews experience by checking out an overview of our mobile and tablet apps here. Stay on top of the poker world from your phone with our mobile iOS and Android app, or fire up our iPad app on your tablet. You can also update your own chip counts from poker tournaments around the world with MyStack on both Android and iOS.