Poker & Pop Culture: Cards, Characters, and Truth-Seeking Fictions

Remember back in school, how eventually most of us discovered we either liked literature and art, or that we were more comfortable with math and science? Usually the grades we earned helped signal our preferences to us, helping us figure out whether or not we preferred stories or statistics, words or numbers.

Then we found poker, which if you think about it equally appeals to both groups. There's enough math involved to satisfy that crowd — and in fact a lot more math than most of us realize, if we're willing to explore. There's also the table talk, the game's rich and unique vocabulary, and, of course, the seemingly endless supply of stories the game produces — some true, some made up, and many a combination of both.

Writers of literature have frequently found poker a fertile source for stories. We've already covered a few examples in this series, highlighting 19th-century poker tales like Bret Harte's "The Outcasts of Poker Flat," Mark Twain's "The Professor's Yarn," the funny "Thompson Street Poker Club" stories of Henry Guy Carleton, among others.

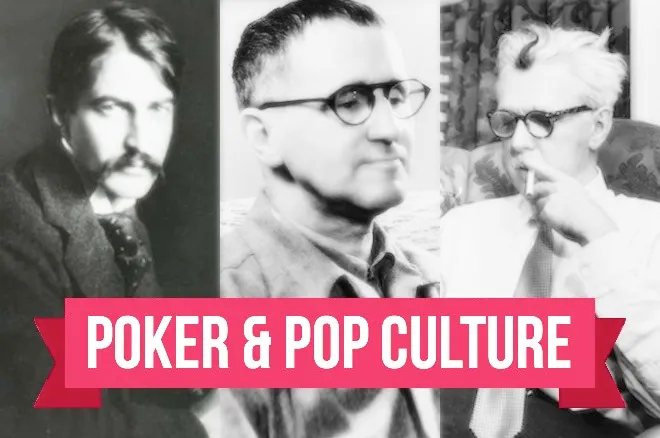

The first decades of the 20th century found more fiction writers inspired by America's favorite card game, among them Stephen Crane, Bertolt Brecht, and James Thurber whose entertaining tales of card-playing we'll highlight today.

All three stories are humorous, containing elements of satire, commentary about middle- and upper-class values and customs, and more general observations about human foibles. They all also well demonstrate how poker can serve as a great storytelling device, with the social customs associated with organizing games as well as the inherent drama of a poker hand being well exploited by these expert fiction writers.

Stephen Crane, "A Poker Game" (1900)

Best known for his Civil War novel The Red Badge of Courage — assigned to some of us during our school days (remember?) — Stephen Crane was a novelist, poet, and short story writer often associated with other "realist" authors among his contemporaries. Sadly Crane's life and output was cut short by tuberculosis at the young age of 28.

Among the first posthumous works of Crane's published was a brief though memorable tale simply titled "A Poker Game." The setting of the game somewhat recalls that of Cassius M. Coolidge's "Dogs Playing Poker" paintings (produced just a few years later) — that is to say, a private game among members of the upper-class such as is suggested in a parodic way by Coolidge's card-playing, cigar-chomping canines.

Crane's imagined game involves a group of wealthy New Yorkers gathered in an uptown hotel room. "Usually a poker game is a picture of peace," the narrator begins, emphasizing the refined, respectable setting before adding what could be called a lengthy defense of poker as worthwhile pursuit — and not at all the morally-questionable, dangerous game others were then describing it.

"Here is one of the most exciting and absorbing occupations known to intelligent American manhood," we're told. "Here a year's reflection is compressed into a moment of thought; here the nerves may stand on end and scream to themselves, but a tranquillity as from heaven is only interrrupted by the click of chips. The higher the stakes the more quiet the scene."

Among those participating in the five-handed game are the real-estate magnate Old Henry Spuytendyvil and the young, naive Bobbie Cinch who inherited his wealth from his recently deceased father.

As Cinch's name might suggest, luck is on his side and while he isn't the most skillful player he finds himself the biggest winner. Meanwhile Old Spuytendyvil — whose name means "spinning devil" — "had lost a considerable amount," the decline in his attitude matching his dwindling chip stack.

A hand of five-card draw arises in which Old Spuytendyvil bets and only Cinch calls. Thanks to an onlooker we learn Old Spuytendyvil was dealt 10♦9♦8♦7♦, and draws one. We also know Young Bob picked up 9♥8♥6♥5♥, and he, too, takes only a single card.

With a "sinister" look Old Spuytendyvil fires a bet, and Cinch pauses to think. "Well, Mr. Spuytendyvil," he finally says, "I can't play a sure thing against you," then tosses in a white chip, just calling his opponent. "I've got a straight flush," says Cinch, showing his completed hand of 9♥8♥7♥6♥5♥.

With a mixture of "fear, horror, and rage," Old Spuytendyvil then shows his hand — J♦10♦9♦8♦7♦. "I've got a straight flush, too!" he yells. "And mine is Jack high!"

An observer then comments on what has happened, and by doing so signals the story's moral to the reader. "Bob, my boy... you're no gambler, but you're a mighty good fellow, and if you hadn't been you would be losing a good many dollars this minute."

In other words, Cinch's decision to "soft play" Old Spuytendyvil and only call with his straight flush saved him from losing more, meaning his generous nature was literally being rewarded. It's a poker hand uncannily matching the game's "gentlemanly" atmosphere. It also suggests a kind of reversal of the old adage "I'd rather be lucky than good," as Young Bob's "goodness" (morally speaking, that is) helped lessen the consequences of his bad luck.

Bertolt Brecht, "Four Men and a Poker Game, or Too Much Luck Is Bad Luck" (1926)

Another story offering a thought-provoking take on luck and poker is the German poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht's darkly humorous "Four Men and a Poker Game, or Too Much Luck Is Bad Luck."

This one features four young athletes, swimmers returning by cruise ship to New York from a swim meet in Havana, all with "money in their pockets" they had won after performing well at the meet. They decide to pass the time with a game of cards, starting out playing only for nickels.

"To tell this story properly really calls for jazz accompaniment," jokes the narrator. "It is sheer poetry from A to Z. It begins with cigar smoke and laughter and ends with a corpse."

Johnny Baker — a.k.a. "Lucky Johnny" — is the worst player of the four, but somehow in this particular game he simply cannot lose. "When Johnny bluffed, the bluff was so ridiculous that no poker player in the world would have dared go along with it. And when anybody who knew Johnny would have suspected a bluff, Johnny would innocently lay a flush on the table."

The stakes increase, and soon Johnny has everyone's money. They begin playing on credit, and here Brecht adds a bit of hyperbole to heighten the drama. The others "would be in hock for years," we're told. "They began to stake their houses. On top of everything else Johnny won a piano.... [One even] offered to play Johnny for his girl."

And Lucky Johnny keeps right on winning. But he has "too big of a heart," we're told, and feeling guilty buys everyone an elaborate and expensive meal. That only angers the others, though, who don't like being "forced to watch their money spent on such senseless tidbits."

The game continues. Johnny starts trying to lose, but the others won't let him. Finally, just an hour from New York, they invite Johnny to go for a walk up on the deck. He doesn't want to go, but they insist.

Before long, Johnny finds himself again in a swimming competition, for the others have heaved him overboard. The three men are left asking each other "whether Johnny Baker... was as good at swimming as he was at winning poker games." The narrator has an answer, suggesting that "nobody can possibly swim well enough to save himself from his fellow men if he has too much luck in this world."

Not unlike Bobbie Cinch, Lucky Johnny and his seemingly endless, incongruously good fortune could be regarded as having "disrupted" the game in the way it upset the others' expectations. Even those who've played poker for a lifetime can find themselves dumbfounded by unanticipated occurrences. While most don't respond by throwing opponents into the ocean, such surprises are nonetheless part of what keeps the game interesting — and a constant wellspring of new stories.

James Thurber, "Everything Is Wild" (1932)

James Thurber's "Everything Is Wild," orginally published in The New Yorker a few years after Brecht's story, offers a different take on a similar idea — namely, that there are people who prefer things to stay the way they are, and anything that upsets the status quo is viewed with a harshly critical eye.

Thurber was a playwright, cartoonist, fiction writer, and journalist, although much of what he did went under the heading of "humorist" as nearly all of it produced lots of grins and laughter among his audience. A frequent source of his humor had to do with the ongoing "battle of the sexes," and that is partly in play in "Everything Is Wild" which features a dinner party involving three couples that ends with a game of poker.

One of those at the party is the curmudgeonly Mr. Brush who doesn't much like socializing, especially among new people ("he never liked anybody he hadn't met before"). He's already in a sour mood, then, when the others decide to break out the cards after the meal. He becomes even more annoyed when the decision is made to play dealer's choice, and the others all insist on playing games with wild cards.

"Seven-card stud," announces one of the women when it is her turn to pick a game. "With the twos and threes wild." The women, we're told, "all gave little excited screams" at the announcement of the wild cards. Meanwhile Mr. Brush — who picked "straight poker" when it was his turn — becomes increasingly exasperated.

Finally he hits on an idea, and when he's the dealer again announces they'll be playing "Soap-in-Your-Eye." When the others say they've never heard of it, he says it is also called "Kick-in-the-Pants" before explaining the rules.

"The red queens, the fours, fives, sixes, and eights are wild," he begins, going on to add how a player drawing a red queen on the second round "becomes forfeit," though "can be reinstated... if on the next round she gets a black four." He deals and keeps adding other options, including having to say "'Back' or 'Right' or 'Left' depending on whether you want to put [a card] back in the deck or pass it to the person at your right or the person at your left" and so on.

Pretty soon everyone is so confused they want to play straight poker, but Mr. Brush insists on carrying the hand through to the end. Three of them end up with royal flushes, "but mine is spades, and is high" Mr. Brush says. "You called me, and that gave me the right to name my suit. I win."

As you've probably figured out, it's all a big ruse designed by Mr. Brush to amuse himself and get back at his wild-card loving opponents. Indeed, when considering his conservative outlook and resistance to change, it's clear that Thurber's title doesn't just refer to a poker game, but to the culture as a whole — it's Mr. Brush's angry response to a world in which "everything" seems as though it has gone "wild."

In each of these stories, poker serves as both a context for characters to interact, as well as a means to motivate and create conflicts between them. The game also provides these fiction writers different, entertaining ways to communicate truths.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America’s Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.

Photos: Crane (left) and Thurber (right), public domain; Brecht (center), CC BY-SA 3.0 de.