Is Straddling a Good or Bad Play?

Poker author Steve Selbrede (The Statistics of Poker, Beat the Donks, Donkey Poker) continues his strategy series on low-stakes Las Vegas cash games.

Straddling is a somewhat controversial topic in the poker world. Tune into an episode of Poker Night in America or watch an old High Stakes Poker rerun and you'll find pros straddling in various high-stakes games. Occasionally you’ll even see double or triple straddles. These guys are top pros, so straddling must be a strong move, right?

Let's consider the question as it applies to the low-stakes cash games we've been considering thus far in the series.

Straddling: Two Types

Although there are many types of straddling, I will limit this discussion to the two types commonly found in Vegas low-stakes games — the under-the-gun and button live straddles.

The UTG straddle is essentially just a third blind paid by the under-the-gun player. Mr. UTG posts his 2BB straddle, the UTG+1 player acts first and the hand proceeds normally.

The straddle is "live," which means that the straddler has the option to raise when the action comes back around to him. The UTG straddle is not a big distortion of a typical $1/$2 game, simply turning it into a $1/$2/$4 game.

Button straddling is similar, except that the button posts the 2BB straddle and (usually) the UTG player acts first. The button acts last unless the pot is raised ahead of him, in which case the action proceeds normally.

The Straddle Tax

My previous article "When Can I Take a Bathroom Break?" showed the true cost of posting our blinds. Simply put, a strong player would earn a small profit from the SB and BB positions if the blinds had been posted by someone else. Instead he loses a substantial amount — about 60 percent of the posted amount, which I call the "blinds tax."

So it stands to reason that a good player would also lose money playing UTG in a "triple-blind" NLH game. We could call this a straddled hand or just a hand played at $1/$2/$4. The UTG player in this game would be paying an additional blinds tax, approximately 60 percent of the size of the third blind (or straddle).

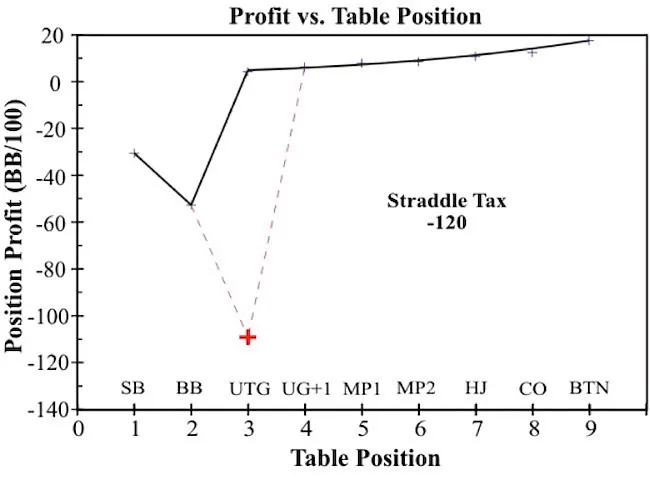

Consider the solid curve appearing below in Figure PN5-1 which shows the average profit made from each position by a "veteran" online NL50 and NL100 player. His average profit gradually decreases as his table position gets worse until reaching the big blind, when his profit takes a big dip. This is the effect of the blinds tax.

If we modify this online game by adding a third 2BB blind, we expect the result depicted by the red dashed lines. Mr. UTG should go from slight profitability to a huge positional loss. (In actuality, the overall curve would shift slightly upward since the extra 2 BB would be profit shared by the rest of the table, especially the button.)

This $1/$2/$4 game is a fair game since every player must pay the third-blind tax. No individual player is inherently penalized, so the best players will still be profitable in the long run.

However, this is not true if we apply this analysis to a straddled $1/$2 game. Now only the straddler pays the 1.2 BB straddle tax (i.e., 60 percent of the 2BB straddle). Mr. Straddler is penalizing himself by an amount greater than the tax he pays from both blinds (about 0.9 BB)! This is why the pros usually will not agree to straddling unless everyone at the table straddles.

Notice that if a player were allowed to straddle in this online game, his straddle tax would wipe out all the profit he expects from playing all of the other positions.

The Button Straddle

Hopefully you are now convinced that straddling UTG is a bad play. "But" (you say), "straddling on the button is different... I have position then. And since position is the key to winning, it’s good for me to play the button at twice the normal stakes."

The problem with this argument is that straddling only provides improved position preflop, not postflop. Most of the value of position is realized postflop, when the pots get bigger and decisions get tougher. If this were not the case, the big blind would be a profitable position since Mr. Big Blind gets to act last preflop. This argument is even less useful for the button straddle, since it only improves our preflop position slightly, and not at all when the pot is raised ahead of us.

Just as it doesn’t matter when we pay the blinds tax (as discussed in my previous article), it also doesn’t matter when we pay the straddle tax. It costs us about 1.2 BB every time we straddle, from whatever position we post it. Once we post it, we can consider that tax to be dead money, available to anyone.

There are many other arguments made to rationalize straddling, which we don’t have space to discuss here. A complete discussion can be found in Chapter 7 of Donkey Poker Volume 1: Preflop.

So the general conclusion is clear... never straddle!

Vegas Straddling

The precise positional profit curve for live Vegas $1/$/2 or $/2/$5 games is not known. But it should be obvious that its general nature should be similar to the online curve. The best players can earn close to 10 BB/hour (about 25 BB/100) playing Vegas $1/$2. So the Vegas curve should be shifted considerably higher on the graph.

That said, the blinds tax and straddle tax will still create big dips in the Vegas curve. So regardless of our poker ability, our profit will dip substantially if we straddle. It is never +EV to put money into the pot blindly.

The Exception to the Rule

There is one scenario where a UTG straddle can make mathematical sense — when we have a potential short-stack shove opportunity against weak and passive opponents. Consider the following scenario:

- Hero is in MP1 and loses a big pot in a Vegas $1/$2 game, leaving only $60 in his stack.

- Hero prefers to wait until he is on the button to chip up, hoping for a short-stack shove opportunity before then. (Hero is very good at short-stack play.)

- Hero is UTG and straddles to $4. His remaining stack is 28 BB, or only 14 "straddles."

- Three players call the straddle. There is now $19 in the pot and Hero has $56 behind, a ratio of only 3-to-1. This is a short-stack shove opportunity for Hero with any two cards.

- Since this is a Vegas $1/$2 game with relatively weak, passive players, Hero will usually take down this pot immediately.

I tested this theory in Vegas during 2016 and found that I took down the pot immediately more than 80 percent of the time. And when called, I usually had reasonable equity, often more than 30 percent.

The key to this play is that our straddle essentially changes the hand from a $2 game to a $4 game, reducing our effective stack by a factor of two. This "Short-Stack Straddle-Shove Scenario" can be a lot of fun to try, since it’s really only applicable when we don’t have that many chips to lose. It works very well against players who won’t call as widely as they should — an extremely common situation in Vegas $1/$2 games.

This can also be thought of as a "game theory optimal" shove against players who fold much more often than game theory requires. It’s analogous to a GTO heads-up shoving range, which can be expanded dramatically when the villain folds much more often than GTO play dictates.

Also in this series...

- Low-Stakes Live Games Differ from Online

- Do You Play Too Many Hands?

- Are You a Position-Dummy?

- When Can I Take a Bathroom Break?

- A Preflop Question: Is Limping Lame?

- Maximizing Expectation When Betting For Value

- Maximizing Expectation When Betting as a Bluff

- Five Weak Reasons to Bet (and One Weak Reason Not To)

- Do You Have 'Jack-O-Phobia'? Playing Pocket Jacks in Live NL Hold'em

Steve Selbrede has been playing poker for 20 years and writing about it since 2012. He is the author of five books, The Statistics of Poker, Beat the Donks, Donkey Poker Volume 1: Preflop, Donkey Poker Volume 2: Postflop, and Donkey Poker Volume 3: Hand Reading.